There have been about a half dozen studies published on Paleo-type diets, starting around 20 years ago. For example, in what sounds like a reality TV show: ten diabetic Australian Aborigines were dropped off in a remote location to fend for themselves, hunting and gathering foods like figs and crocodiles.

In Modern Meat Not Ahead of the Game, my video on wild game, I showed that kangaroo meat causes a significantly smaller spike of inflammation compared to retail meat like beef. Of course, ideally we’d eat anti-inflammatory foods, but wild game is so low in fat that you can design a game-based diet with under 7 percent of calories from fat. Skinless chicken breast, in comparison, has 14 times more fat than kangaroo meat. So you can eat curried kangaroo with your cantaloupe (as they did in the study) and drop your cholesterol almost as much as eating vegetarian.

So, how did the “contestants” do? Well, nearly anything would have been preferable to the diet they were eating before, which was centered on refined carbs, soda, beer, milk, and cheap fatty meat. They did pretty well, though, showing a significantly better blood sugar response—but it was due to a ton of weight loss because they were starving. Evidently, they couldn’t catch enough kangaroos, so even if they had been running around the desert for seven weeks on 1,200 daily calories of their original junky diet, they may have done just as well. We’ll never know, though, because there was no control group.

Some of the other Paleo studies have the same problem: They’re small and short with no control groups, yet still report favorable results. The findings of one such study are no surprise, given that subjects cut their saturated fat intake in half, presumably because they cut out so much cheese, sausage, or ice cream. In another study, nine people went Paleo for ten days. They halved their saturated fat and salt intake, and, as one might expect, their cholesterol and blood pressure dropped.

The longest Paleo study had been only 3 months in duration, until a 15-month study was conducted—but it was done on pigs. The pigs did better because they gained less weight on the Paleo diet. Why? Because they fed the Paleo group 20 percent fewer calories. The improvement in insulin sensitivity in pigs was not reproduced in a study on people, however. Although, there were some benefits like improved glucose tolerance, thanks to these dietary changes: The Paleo group ate less dairy, cereals, oil, and margarine, and ate more fruits and nuts, with no significant change in meat consumption.

A follow-up study also failed to find improved glucose tolerance in the Paleo group over the control group, but did show other risk factor benefits. And no wonder! Any diet cutting out dairy, doughnuts, oil, sugar, candy, soda, beer, and salt is likely to make people healthier and feel better. In my video Paleo Diet Studies Show Benefits, you can see a day’s worth of food on the Standard American Diet, filled with pizza, soda, burgers, processed foods, and sweets, versus a Paleo diet, which, surprisingly, has lots of foods that actually grew out of the ground.

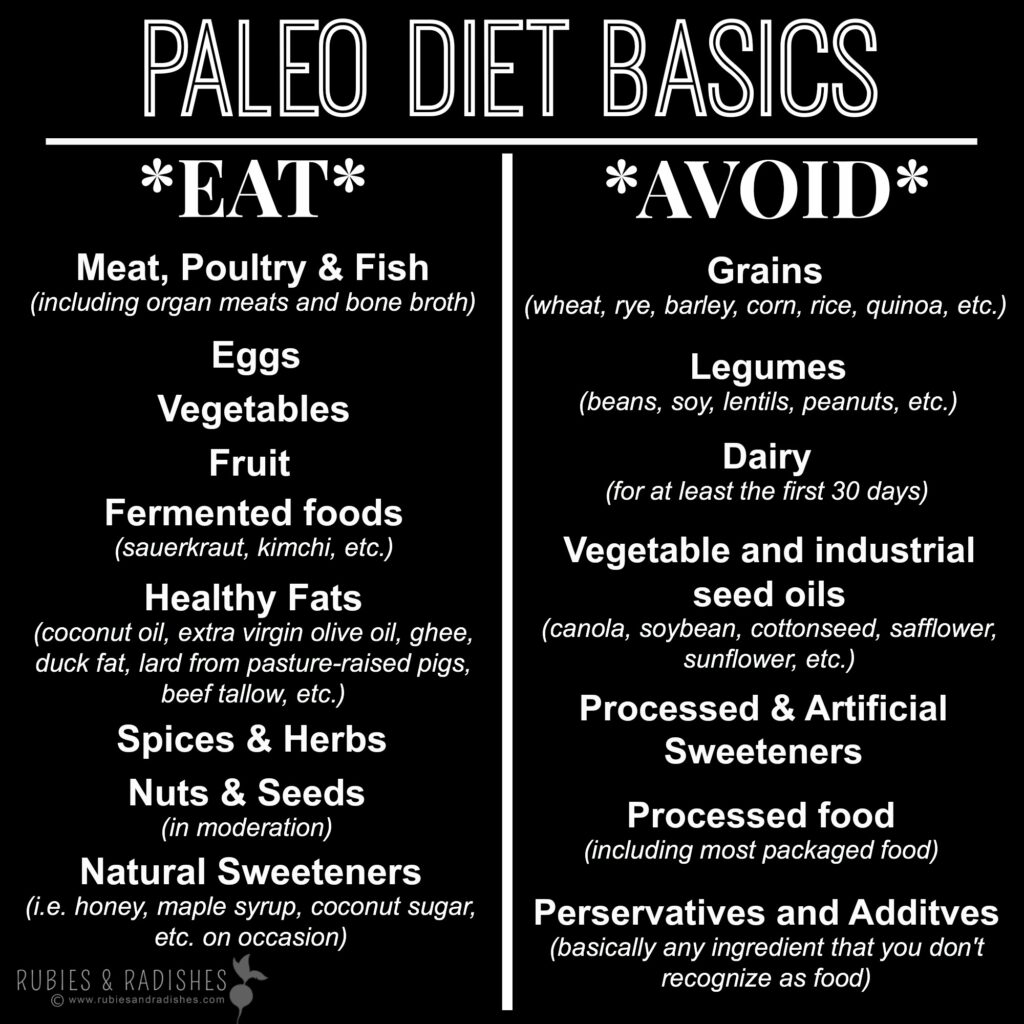

But the Paleo diet also prohibits beans. Should we really be telling people to stop eating beans? Well, it seems hardly anyone eats them anyway. Only about 1 in 200 middle-aged American women get enough, with more than 96 percent of Americans not even reaching the minimum recommended amount. So telling people to stop isn’t going to change their diet very much. I’m all for condemning the Standard American Diet’s refined carbs, “nonhuman mammalian milk”, and junk foods, but proscribing legumes is a mistake. As I’ve noted before, beans, split peas, chickpeas, and lentils may be the most important dietary predictor of survival. Beans and whole grains are the dietary cornerstones of the longest living populations on Earth. Plant-based diets in general and legumes in particular are a common thread among longevity blue zones around the world.

The bottom line may be that reaching for a serving of kangaroo may be better than a cheese danish, “but foraging for…[an] apple might prove to be the most therapeutic of all.”