“How can I be eating so little, and still gaining weight?”

Have you ever felt this way? (Or had a client who has?)

In my years as a coach, it’s a question that’s come up time and time again—from both clients and fellow coaches.

They’re confused. Frustrated. Maybe even angry. (Or certainly “hangry.”)

Despite doing everything they can, including eating less—maybe a lot less—they’re still not losing weight. In fact, they might even be gaining.

Do a quick Internet search and you’re bound to find lots of explanations.

Some folks say that the laws of energy balance apply, and that people aren’t counting calories properly. Others call it “starvation mode”, or some weird metabolic or hormonal problem.

So what’s the deal? Is there something wrong with them? Are their bodies broken? Is it all in their heads?

Or can you actually gain weight from eating too little?

Let’s find out.

Truth: Thermodynamics don’t lie.

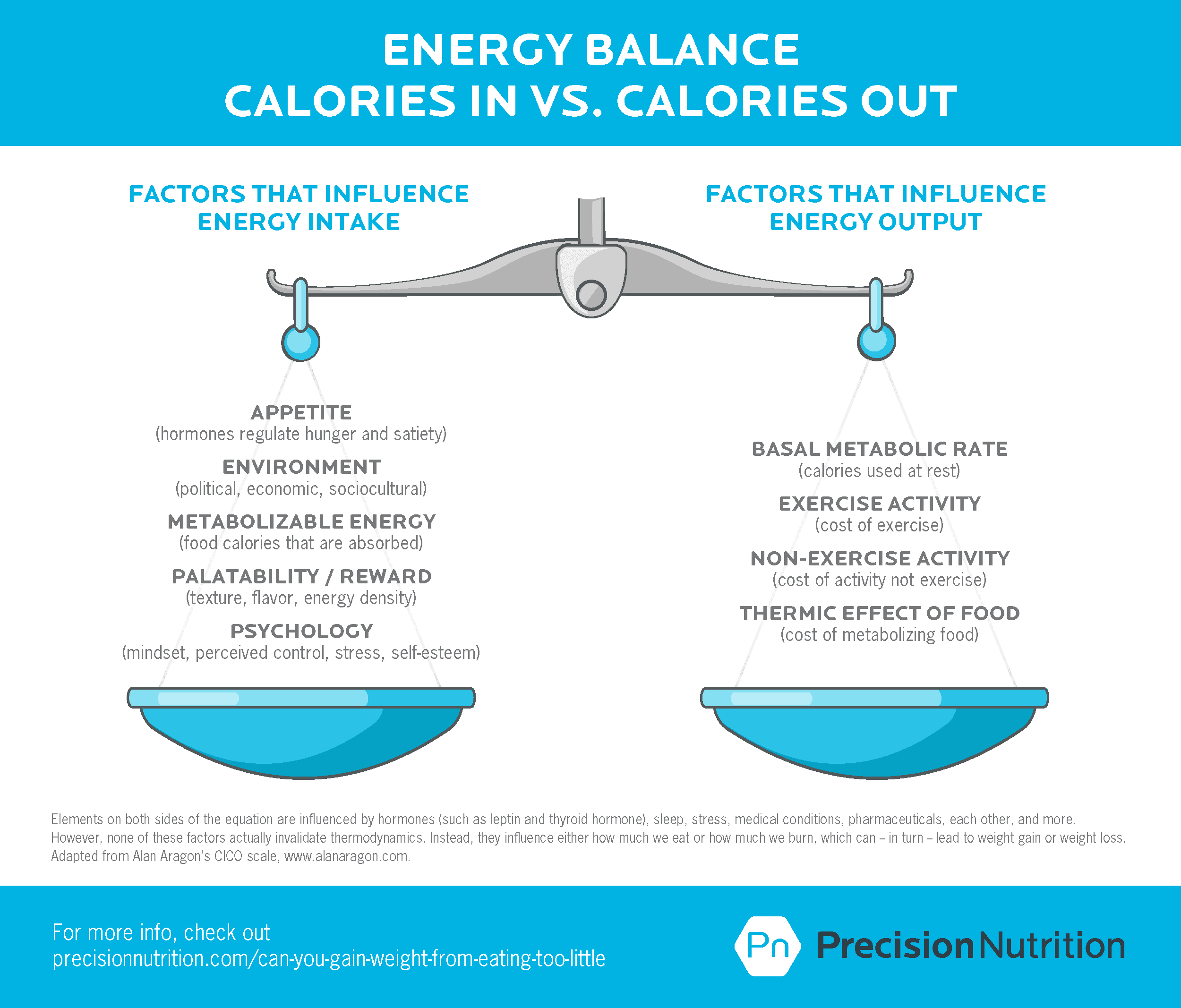

You’ve probably heard the phrase—the laws of thermodynamics—before. Or maybe you’ve heard it as energy balance. Or “calories in, calories out.”

Let’s break down what it actually means.

Thermodynamics is a way to express how energy is used and changed. Put simply, we take in energy in the form of food, and we expend energy through activities like:

- basic metabolic functions (breathing, circulating blood, etc.)

- movement (daily-life activity, purposeful exercise, etc.)

- producing heat (also called thermogenesis)

- digestion and excretion

And, the truth is…

Energy balance (calories in, calories out) does determine bodyweight.

- If we absorb more energy than we expend, we gain weight.

- If we absorb less energy than we expend, we lose weight.

This has been tested over and over again by researchers, in many settings.

It’s as close as we can get to scientific fact.

Sure, there are many factors that influence either side of this seemingly simple equation, which can make things feel a little confusing:

However, humans do not defy the laws of thermodynamics.

But what about unexplained weight changes? That time you ate a big dinner and woke up lighter? When you feel like you’re “doing everything right” but you’re not losing weight?

Nope, even if we think we’re defying energy in vs. energy out, we’re not.

And what about that low carb doctor who implies that insulin resistance (or some other hormone) mucks up the equation?

While hormones may influence the proportions of lean mass and fat mass you gain or lose, they still don’t invalidate the energy balance equation.

Yet, as the title of the article suggests, it is easy to understand why folks—even internet-famous gurus and doctors—get confused about this.

One reason why…

Measuring metabolism is tricky.

The fact is, your exact metabolic demands and responses aren’t that easy to measure.

It is possible to approximate your basal metabolic rate—in other words, the energy cost of keeping you alive. But measurements are only as good as the tools we use.

When it comes to metabolic measurement, the best tools are hermetically sealed metabolic chambers, but not many of us hang out in those on the regular.

Which means, while we may have our “metabolism” estimated at the gym, or by our fitness trackers, as with calorie counts on labels, these estimates can be off by 20-30 percent in normal, young, healthy people. They’re probably off by even more in other populations.

Of course, if we could accurately measure how much energy you’re expending every day, and then accurately measure exactly how much energy you’re taking in and absorbing, we could decide whether you were truly “eating too little” for your body’s requirements.

But even if we could know this outside the lab, which we can’t, it wouldn’t be useful. Because energy output is dynamic, meaning that every variable changes whenever any other variable changes (see below).

In other words, unless we can exactly measure energy inputs and outputs from minute to minute, we can’t know for sure what your metabolism is doing and how it matches the food you’re eating.

So, most of the time, we have to guess. And our guesses aren’t very good.

You Might Also Like:

Not only that, but the idea of “eating too little” is subjective.

Think about it. By “eating too little”, do you mean…

- Eating less than normal?

- Eating less than you’ve been told to eat?

- Eating less than feels right?

- Eating less than you need to be healthy?

- Eating less than your estimated metabolic rate?

- Eating less than your actual metabolic rate?

And how often does that apply? Are you…

- Eating too little at one meal?

- Eating too little on one day?

- Eating too little every day?

- Eating too little almost every day but too much on some days?

Without clarity on some of these questions, you can see how easy it is to assume you’re “eating too little” but still not eating less than your actual energy expenditure, even if you did some test to estimate your metabolic rate and it seems like you’re eating less than that number.

Most times, the problem is perception.

As human beings, we’re bad at correctly judging how much we’re eating and expending. We tend to think we eat less and burn more than we do—sometimes by as much as 50 percent.

(Interestingly, lighter folks trying to gain weight often have the opposite problem: They overestimate their food intake and underestimate their expenditure.)

It’s not that we’re lying (though we can sometimes deceive ourselves, and others, about our intake). More than anything, it’s that we struggle to estimate portion sizes and calorie counts.

This is especially difficult today, when plates and portions are bigger than ever. And energy-dense, incredible tasting, and highly brain-rewarding “foods” are ubiquitous, cheap, and socially encouraged.

When folks start paying close attention to their portion sizes using their hands or food scales and measuring cups, they are frequently shocked to discover they are eating significantly more than they imagined.

(I once had a client discover he was using ten tablespoons of olive oil—1200 calories—rather than the two tablespoons—240 calories—he thought he was using in his stir-fry. Oops.)

At other times, we can be doing everything right at most meals, but energy can sneak when we don’t realize it.

Here’s a perfect story to illustrate this.

A few years ago Dr. Berardi (JB, as he’s known around here) went out to eat with some friends at a well-known restaurant chain. He ordered one of their “healthier” meals that emphasized protein, veggies, and “clean” carbs. Then he finished off dinner with cheesecake.

Curious about how much energy he’d consumed, he looked it up.

Five. Thousand. Calories.

Incredibly, he hadn’t even felt that full afterwards.

If the calorie content of that one meal surprised someone with the expertise and experience of JB, how would most “normal” eaters fare? Good luck trying to “eyeball” things.

Also imagine a scenario where you were under-eating almost every meal during the week and maintaining an estimated negative energy balance of about -3,500 calories. Then, during one single meal, a “healthy” menu option plus dessert, you accumulated 5,000 calories.

That one meal would put you in a theoretically positive energy balance for the week (+1,500 calories), leading to weight gain!

Seriously, how would you feel if, after eating 20 “perfect” meals in a row and 1 “not so bad” meal, you gained weight? You’d probably feel like your metabolism was broken.

You’d probably feel like it’s possible to gain weight from eating too little.

But, again, the laws of thermodynamics aren’t broken. Rather, a whole bunch of calories snuck in without you realizing it.

Even more, the dynamic nature of metabolism can be confusing.

Another reason it can be easy to believe you gained weight eating too little (or at least didn’t lose weight when eating less) is because your metabolism isn’t like a computer.

For instance, you might have heard that one pound of fat is worth 3,500 calories, so if you cut 500 calories per day, you’ll lose one pound per week (7 x 500 = 3,500).

(Unless, of course, you downed 5,000 calories in a single meal at the end of the week, in which case you’d be on track to gain weight).

Except this isn’t how human metabolism works. The human body is a complex and dynamic system that responds quickly to changes in its environment.

When you under-eat, especially over a longer period (that part is important), this complex system adapts.

Here’s an example of how this might play out:

- You expend less energy in digestion because you’re eating less.

- Resting metabolic rate goes down because you weigh less.

- Calories burned through physical activity go down since you weigh less.

- Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (daily-life fidgeting, movement) goes down and you expend less energy through the day.

- Your digestion slows down, and you absorb more energy from your food.

Your body will also adjust hormonal feedback and signaling loops. For instance:

- Appetite and hunger hormones go up (i.e. we want to eat more, are more stimulated by food cues, may have more cravings).

- Satiety hormones go down (which means it’s harder for us to feel full or satisfied).

- Thyroid hormones and sex hormones (both of which are involved in metabolic rate) go down.

Your planned 500 calorie daily deficit can quickly become 400, 300, or even 200 calories (or fewer), even if you intentionally exercise as much as you had before.

And, speaking of exercise, the body has similar mechanisms when we try to out-exercise an excessive intake.

For example, research suggests that increasing physical activity above a certain threshold (by exercising more) can trigger:

- More appetite and more actual calories eaten

- Increased energy absorption

- Lowered resting or basal metabolism

- Less fidgeting and spontaneous movement (aka NEAT)

In this case, here’s what the equation would look like:

These are just two of the many examples we could share.

There are other factors, such as the health of our gastrointestinal microbiota, our thoughts and feelings about eating less (i.e. whether we view eating less as stressful), and so on.

The point is that metabolism is much more complicated (and interdependent) than most people realize.

All of this means that when you eat less, you may lose less weight than you expect. Depending how much less you eat, and for how long, you may even re-gain weight in the long run thanks to these physiological and behavioral factors.

Plus, humans are incredibly diverse.

Our metabolisms are too.

While the “average” responses outlined above are true, our own unique responses, genetics, physiology, and more means that our calorie needs will differ from the needs of others, or the needs predicted by laboratory tools (and the equations they rely on).

Let’s imagine two people of the same sex, age, height, weight, and lean body mass. According to calculations, they should have the exact same energy expenditure, and therefore energy needs.

However, we know this is not the case.

For instance:

- Your basal metabolic rate—remember, that’s the energy you need just to fuel your organs and biological functions to stay alive—can vary by 15 percent. For your average woman or man, that’s roughly 200-270 calories.

- Genetic differences matter too. A single change in one FTO gene can be an additional 160 calorie difference.

- Sleep deprivation can cause a 5-20 percent change in metabolism, so there’s another 200-500 calories.

- For women, the phase of their menstrual cycle can affect metabolism by another 150 calories or so.

Even in the same individual, metabolism can easily fluctuate by 100 calories from day to day, or even over the course of a day (for instance, depending on circadian rhythms of waking and sleeping).

Those differences can add up quickly, and this isn’t even an exhaustive list.

If you want to dig really deep into the factors that influence our energy balance, check this out:

In the end, hopefully you can see how equations used to predict calorie needs for the “average” person might not be accurate for you. And that’s why you could gain weight (or not lose weight) eating a calorie intake that’s below your measured (estimated) expenditure.

It’s also why some experts, who aren’t knowledgeable about the limitations of metabolic measurement, will try to find all sorts of complicated hormonal or environmental causes for what they think is a violation of thermodynamics.

The answer, however, is much simpler than that.

The estimates just weren’t very good.

And yes, water retention is a thing.

Cortisol is one of our “stress hormones”, and it has effects on our fluid levels.

Food and nutrient restriction is a stressor (especially if we’re anxious about it). When we’re stressed, cortisol typically goes up. People today report being more stressed than ever, so it’s easy to tip things over into “seriously stressed”.

When cortisol goes up, our bodies may hold onto more water, which means we feel “softer” and “less lean” than we actually are. This water retention can mask the fat loss that is occurring, making it seem like we aren’t losing fat and weight, when in fact we are.

Here’s an example.

A good friend of mine (and former high school hockey teammate) was struggling to make the NHL. He had played several seasons in the AHL (one step down from the NHL) and had just been called up to the pros.

The NHL club wanted him to stay below 220 lbs (100 kg), which was a challenge for him at 6’2”. He found that eating a lower-carb diet allowed him to maintain a playing weight around 218 lbs.

Yet his nutrition coach told him it was OK to have some occasional higher-carb days.

Unfortunately for him, he had one of these higher-carb days—going out for sushi with his teammates—right before his first NHL practice.

The next day, when reporting to the NHL team, he was called into the GM’s office to get weighed. He was 232 lbs (105 kg).

Thanks, carbs and salt!

My friend was crushed. Even worse, two days later he was back to 218 lbs.

OK, but what if I track my intake and expenditure meticulously?

You might be nodding your head, beginning to realize how complex metabolism is. How inaccurate calorie counts can be. How variable we all are. How much the body seeks to maintain the status quo. And how poor we are at estimating our own intake and expenditure.

But what if you are meticulously tracking intake? Logging your meals? Counting your steps? Even hitting a local research lab to measure your metabolism? And things still aren’t adding up?

Well, it goes back to what we’ve discussed so far:

- The calorie counts of the foods you’ve logged might be higher than expected, either because of erroneous labeling or because of small errors in your own measurement.

- Your energy needs might be lower than calculated (or even measured). This may be because…

- You’re expending less energy through movement than your fitness tracker or exercise machine suggests.

- You have less lean mass as you think, or it may not be as energy-consuming as you expect.

- You’re absorbing more energy in digestion than you realize (for instance, if your gastrointestinal transit time is slow, or your microbiota are really good at extracting nutrients).

Maybe you’re just missing some data.

As mentioned above, while you’re probably not outright lying, it could be that you’re also “forgetting” to account for the few bites of your kids’ chicken nuggets that you didn’t want to go to waste. Or that extra spoonful of peanut butter. Or the large glass of wine you counted as a ‘medium’. Likewise, the calorie counts on those food labels can be (and often are) off.

Maybe you’re counting your workout as high intensity, even though you spent much of it sitting on a bench between low-rep strength sets. Maybe you were so hungry afterwards, you ate more than you intended (but figured it was all going to muscle-building, so no biggie).

It happens; we’re all human.

Measuring and tracking your energy intake carefully can help.

When we measure and track for a while, we become more aware of what we’re eating, get a more realistic idea of our portion sizes, and help ourselves be consistent and accountable.

But measuring and tracking definitely is not a perfect strategy.

It can be stressful and time-consuming. Most people don’t want to do it forever.

And it may misrepresent the “exact” calories we consume versus the “exact” calories we burn, which can lead us to believe we’re eating less than we’re burning, even when we’re not.

What about legitimate medical problems?

Whenever we arrive at this point of the discussion folks usually ask about whether underlying health problems, or medications, can affect their metabolism, weight, and/or appetite.

The answer is yes.

This includes things like polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), certain pharmaceuticals (corticosteroids or birth control), severe thyroid dysfunction, sex hormone disruption, leptin resistance, and more.

However, this is less common than most people think, and even if you do have a health issue, your body still isn’t breaking the laws of thermodynamics.

It’s just—as discussed above—that your calorie expenditure is lower than predicted. And a few extra calories may be sneaking in on the intake side.

The good news: weight loss is still possible (albeit at a slower pace).

If you truly feel that you are accurately estimating intake, exercising consistently at least 5-7 hours a week, managing your sleep and stress, getting expert nutritional coaching, and covering absolutely all the fundamentals, then it may be time to consider further conversations and testing with your doctor.

So what can you do?

If you feel your intake is less than your needs, (in other words, you’re eating what feels like ‘too little’) but you still aren’t losing weight, here are some helpful next steps to try.

Measure your intake.

Use whatever tools you prefer. Your hands, scales and spoons, pictures, food logs, etc. It doesn’t matter.

Track your intake for a few days or a full week, to see if it adds up to what you “thought” you were eating. We are often surprised.

Sometimes, just the act of tracking increases our awareness of our intake, which helps us make better choices.

Be compassionate with yourself.

It may feel like being strict or critical is a good approach, but it isn’t. It just makes you more stressed out.

Conversely, research shows that being kind and gentle with yourself (while still having some grown-up honesty about your decisions) helps you have a healthier body composition, make wise food choices, stick to your fitness goals better, feel less anxious and stressed, and have a better relationship with food overall.

There are going to be meals or days where you don’t eat as you “should”. It’s OK. It happens to everyone. Recognize it, accept it, forgive yourself, and then get back on track.

Choose mostly less-processed whole foods.

Foods that aren’t hyper-rewarding or hyperpalatable are harder to over-eat. They don’t cause hypothalamic inflammation and leptin resistance.

They have lots of good stuff (vitamins, minerals, water, fiber, phytonutrients, disease-fighting chemicals, etc.) and are usually lower in calories.

And they are usually far better at keeping you full and satisfied.

Choose whole foods that you enjoy and will eat consistently.

Play with macronutrient levels.

Some people respond better to more carbs and fewer fats. Others respond better to higher fats and few carbs.

There’s no single best diet for everyone. We all have different preferences, and even different responses to foods and macronutrients. So play with this a bit, and find what works for you.

Own your decisions.

Let your adult values and deeper principles guide you when you sit down to eat. Make food choices by acknowledging the outcome you would expect.

Avoid playing mental games like “If I’m ‘good’ then I get to be ‘bad”, or “If I pretend I didn’t eat the cookies, then it didn’t happen”.

Face your behavior with open eyes, maturity, and wisdom.

Accept that all choices have consequences.

And appreciate that it’s OK to indulge sometimes.

If you are still having trouble, get coaching.

Behavior change and sustained weight loss are hard. Especially when we try to go it alone.

Seek out a qualified and compassionate coach or professional who can help you navigate these tricky waters.

A final note on body composition.

Before wrapping up I wanted to mention something important.

In this article I decided to focus only on the body weight implications of the energy balance equation because that’s all the equation really describes (i.e. net transfers of energy).

Changes in body composition (i.e. your relative proportions of lean tissue and body fat) are, if you can believe it, much more complicated and far less comprehensively studied.

This article was originally published here